Wilson in his book “Biophilia” (1984, page 1), defined biophilia as “the innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes”, as a love of life, a sense of place and connection. He utilized the term “biophilia” to describe the “deep feelings of connection to nature during a period of exploration and immersion in the natural world” (Wilson 1984, Page.1). He came with an interesting view on environment ethic or value which human assign to other species, ecosystem or natural phenonema generally. In addition, according to him, humans were born with brain and mind which only develop normally when having the contact with nature (Wilson 1984).

According to Beatley (2011; Newman 2013), a biophilic city is at its heart biodiverse, full of nature where the residents could live and feel rich nature including trees, plants, and animals. Nature as mentioned here includes the small and large such as the trees, the plants, even the microorganisms to the large natural features and ecosystems which form the character of the city. He emphasizes that the purpose of the biophilic city is not only to cherish the existing nature; it works hard to restore and repair what has been lost in order to add more form of nature into the design.

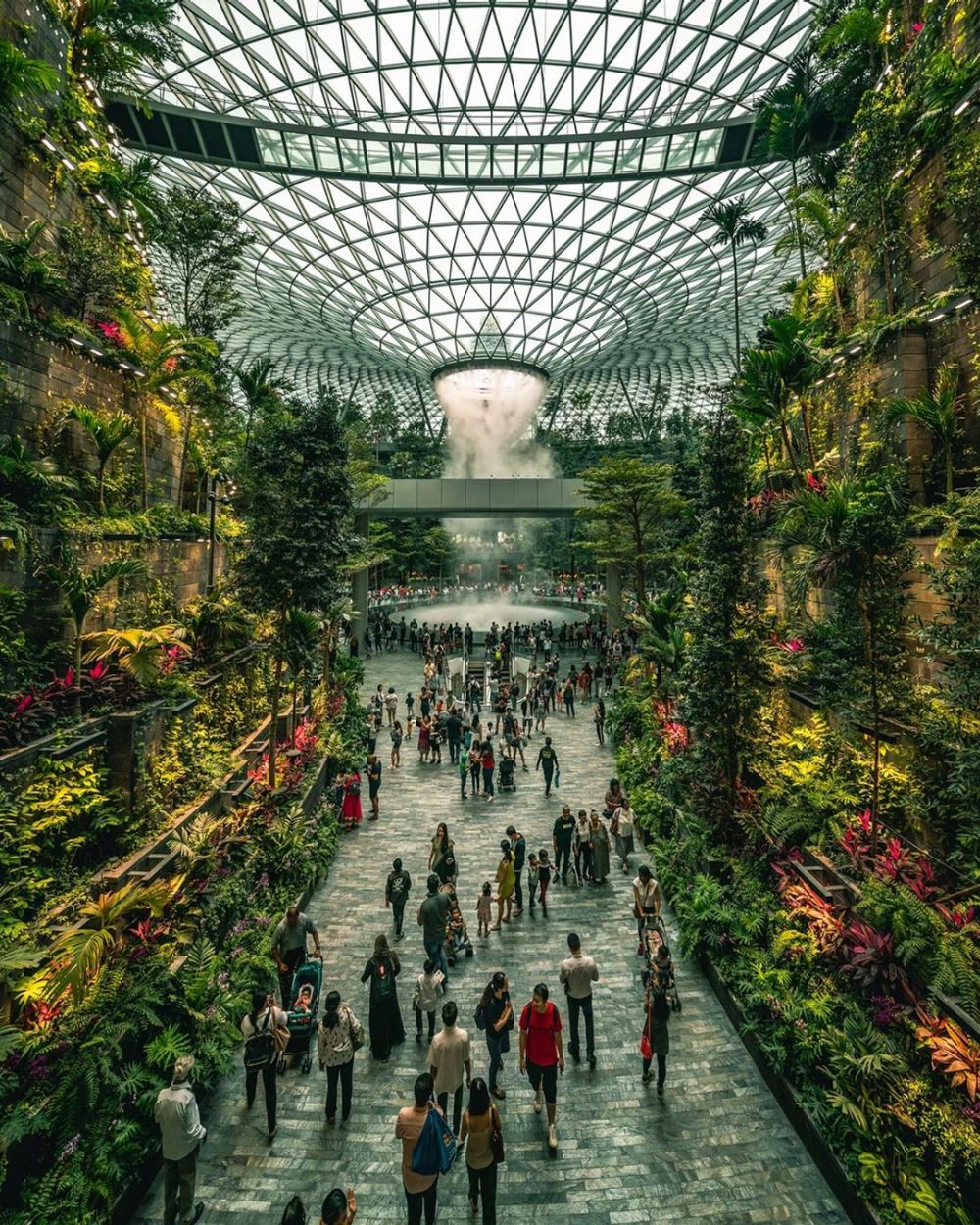

For Newman (2013), the biophilic city is one which has unique and diverse environments, rich in nature. These cities are designed and developed to foster love with nature into daily life; the place where people can enjoy nature and create a relationship with nature around living environments. According to him, the concept of green urbanism refers to settlements that are smart, secure, and sustainable (Newman 2013). An important innovation in green urbanism is the biophilic city (Figure 4).

With the rapid increase of urbanization, especially in developing countries, Asian cities are a major focus in the twenty-first century. These cities could learn from the European cities, which are reported to have done well in creating green urbanism. European cities have become the leading examples for the world in terms of the biophilia concept and its implications (Beatley 2012). The importance of biophilic cities is not only counted by green city designs or the number of green walls/ rooftop gardens. It is not only how the city could encourage urban agriculture or have as much as tree canopy as possible but it is also most important how the people living in that city could enjoy and live with that nature. This connection is the most important aspect of the biophilic city (Newman 2013).

These relationships form by various factors but the love of nature (Louv 1996) developed by the interaction daily with the surrounding living environment. Therefore, the extent to which the connection between the biophilic city with humans is the key factor to build the prosperity, identity and unique nature of a biophilic city will be the focus of this research.

Biophilic city. Source: Biophilic Cities. 2020

Key concepts

1 Green Urbanism

Green urbanism is understood as urban areas which take nature as the centre of design and development:

Green urbanism is by definition interdisciplinary; it requires the collaboration of landscape architects, engineers, urban planners, ecologists, transport planners, physicists, psychologists, sociologists, economists, and other specialists, in addition to architects and urban designers (Lehmann 2011, page 3).

The main purpose of green urbanism is to minimize the use of energy, water, and materials. In addition, it also promotes the reuse and recycling from all activities and products as well as economic processes in daily life. In a green city, people can feel and explore nature as the key component of the city’s design. Green urbanism is not only limited to green landscapes or architecture, but it also includes the relationship with humans in that environment and it helps to transform the green design in order to foster people’s connection with the living environment (Beatley 2013).

According to Lehmann (2011), there are three pillars of green urbanism which interact with each other. They are energy and material; water and biodiversity; urban planning and transport which include key components to form the concept of green urbanism. The details of each pillar which contain different elements are shown in Figure 1.

Green urbanism describes settlements that are smart, secure, and sustainable (Newman 2013). He points to seven emerging aspects of innovation in green urbanism involving archetypal cities and one of them is the biophilic city which is based on the biophilia hypothesis expanded on below.

2 Biophilia

In this century, it is easy to recognize several cities, especially in Europe, which are an integrated system of parks, open space, green walls, green rooftops, and greenways or tree canopy. It is also more evident that people now bring nature into housing or urban design and enhances communities in biological ways. The landscape architects and urban designers, or architects are responsible for providing an ecological approach in designing our urban landscapes (Newman 2013).

The term “biophilia”, first mentioned by the social psychologist Erich Fromm, meant “love of life or living system” (Fromm 1973). It was then popularized by an American entomologist Edward O. Wilson as an essence of our humanity. Wilson (1984) claimed that because of humanity, species diversity was created, emphasizing that when people seek to explore nature, that exploration will engage and foster the things close to the human heart and spirit. Wilson also described biophilia as “humans, as part of nature, want to be around nature” (1984, page 4), meaning that humans have an affinity with nature. Additionally, “the naturalist’s vision is a specialized product of a biophilic instinct shared by all, that can be elaborated to benefit more and more people” (Wilson 1984). Therefore, because of the relationship between nature and humans, the need for nature exists in our daily life and biophilic design emerged. Biophilic designs create the biophilic cities, which integrate nature into human’s modern life with the need to include nature in society.

According to Kellert and Wilson (1995), there are nine hypothesised dimensions of biophilia. He used these to describe how humans’ deep dependence on nature may constitute the basics for a meaningful and fulfilling human existence, and how the pursuit of self-interest may constitute the most persuasive argument for persons to develop a conservation ethic — where people exploitate and use the resource in a mindful and respectful way to maintain the health of the natural world. Each of these dimensions are important and interact each other. In order to express the biophilia concept, people can experience it in the biophilic city by the biophilic design.

3 Biophilic Design.

Based on the concept of Restorative Environmental Design (RED) (Keller 2015), biophilic design is inspired by nature using elements that utilize its components and principles (Figure 2). It aims to restore natural patronage in the built environment in order to maintain, reestablish, and enhance our physiological, cognitive, and psychological connection to the natural world.

The biophilic design focuses not only on the presence of nature but also on the content, the relationship, and connection with the scene. The main purpose of biophilic design is to create a living environment where people can live and feel “emotional architecture” (Aleph 2014). By this he means that it will bring a sense of place for humans to live there. As a result, people can connect and immerse themselves in a living condition to build up a sustainable and resilient community. Biophilic design has health, environmental value, cultural, economic, and ecological benefits (Browning, Clancy and Ryan 2014). Those benefits are a precondition for people to have a healthy life where they can honor the environmental value, build up the culture, and strengthen resilient communities in order to create a resilient city.

4 Resilient City

Resilience is the ability to handle disturbances or shocks; after the shocks happen, if a city or community has the ability to re-organize to keep the same functions, structure and feedback then they can keep the same identity (Cork 2008). Therefore, a resilient city is one that can withstand and recover from damage or disaster (Stockholm Resilience Centre 2015).

There are some specific features or indicators of a resilient city. Two main things should be considered — awareness and being in action (Bolter 2018; Smartcitydive 2018). First, awareness of the risks of the situations is needed to ensure we are ready to undertake actions to overcome the challenges to reduce potential damage. In a community, its history and culture will help to determine the direction and strategy to act according to the situation. There would be different actions and plans to deal with different shocks or risks based on the community’s history and culture. If we could have a deep understanding of the history and we have a sense of the community culture, we will easily get to know the region’s characteristics. As a result, this understanding will be the key factor to decide how and what to do to keep the resilience of its region.

Secondly, the connection between the region and community plays an important role in resilience. The connection will reflect how that community reacts to shocks or disturbances, how they want to solve the problem in their own ways. It is about the attachment among the members of the community; how they build their relationship into the system, how the system is built to react with the disturbance, means that they may prepare for the changes that may happen. Hopkins (2009) shows that diversity is one of three dimensions of resilience, which is the connection between elements. In that sense, the flexibility of the community will determine the way it responds to the shocks or disturbances. This flexibility expresses in various ways — either the community is proactive in problem solving or not, or they have resources ready to deal with changes and crises when they happen. This ability also shows the awareness and the ability of the system in terms of dealing with the situation. Each of the mentioned indicators are equally important. Therefore, building the resilience of the community is a crucial step for the system to face future sustainability as well as create urban sustainability.

5 Urban Sustainability

Urban sustainability can be understood as the city which minimizes the inputs and outputs (UNEP 2015). Sustainable cities, urban sustainability, (or eco-city) are ones designed with consideration for social, economic and environmental impacts , as well as resilient habitats for existing populations, without compromising the ability of future generations to experience the same. This means they use fewer resources and create less waste. These cities encourage people who are dedicated to the minimization of required inputs of energy, water, food, waste, the output of heat, air pollution — carbon dioxide and water pollution (UNEP 2015). However there is no single model of a sustainable city; rather they are a choice of different solutions designed to support long-term ecological balance (Oxfam Australia 2020). There are some fundamentals that are critical to the classification of every sustainable city which will be addressed below.

Firstly, in a sustainable city, there is access to public resources. It means that the city can provide guaranteed access to quality education, safe health centres, easy to access public transportation, garbage collection services, safety, and good air quality, among other modern living necessities. Secondly, the city needs to have urban renewal actions such as public streets, squares, parks, urban spaces as well as modern irrigation and waste management. These practices are vital aspects of sustainable living (Oxfam Australia 2020). Next, minimising waste is another important indicator to identify a sustainable city. In addition, it also needs to favour ethical consumption by promoting local food production to reduce imports. Having local consumption is the best way to reduce food miles ( the number of miles over which a food item is transported during the journey from producer to consumer — Stanley 2014, page 9). As a result, it also reduces waste and another transportation emission which has negative impacts on the living environment. Finally, living with the “reduce, reuse, recycle” concept people can help each other to minimise the inputs and outputs which put heavy stress on nature. Those are the fundamental criteria to identify or to build up for urban sustainability (Oxfam Australia 2020).

The connections between the above elements are essential and play an important role in building urban sustainability. All of the elements (buildings, streets, public spaces, natural spaces) of the urban environment are emotional infrastructure (Oxfam Australia 2020). They influence how we feel and treat each other. Happiness comes from an urban environment that nurtures emotion. The connection and relationship between the community members make the city unique and special. It aids feeling a sense of dignity and equality, of being included, genuine freedom to move, trusting, meaningful relationships with other people, contact with nature beauty (Allan Johnstone’s lecture May 2019).

In the context of Western Australia, The Inquiry’s (2003) “Sustainable Cities 2025 Discussion Paper” highlights seven key components to sustainable urban communities:

1) Sustainable transport, street patterns and movements

2) Urban form&housing, a mix of different land uses; density and housing diversity, architecture

3) Ensuring equitable, efficient, environmentally sustainable use of energy

4) Using and reusing water sustainably; water sensitive city

5) Significant heritage and urban green space; reserving bushland; nature and green space

6) Minimise waste

7) Happiness, beauty, interesting moments, and the need to not feel excluded.

In urbanization time, the city has to face with different challengings, especially poverty and pollution. Among the innovation sollutions beside biophilic design, there is another type of urban forms which can contribute to several criteria of a sustainable city such as providing green spaces, basic living neccessity (food) and sustainable water management. That is urban agriculture.

6 Urban Agriculture

Urban agriculture may be understood as the growing of plants and raising of animals within and around cities (Figure 3). It provides food products from different types of crops (e.g. grains, root crops, vegetables, mushrooms, fruits), animals (e.g. poultry, rabbits, goats, sheep, cattle, pigs, guinea pigs, fish) as well as non-food products (e.g. aromatic and medicinal herbs, ornamental plants, tree products) (FAO 2019). Utilising urban agriculture in the process of urbanization plays a significant role in sypplying food demands for the growing urban population as well as contributing to the environmental, social, economic, education and health benefits. These types of activities may also help to reduce the “food miles”, carbon emission from transportation and help to improve the community relationship when interacting with nature and agriculture, helping to tackle climate change, food security and access to food in the cities.

Urban agriculture not only creates environmental, educational, cultural, health and social benefits but also has economic benefits, creating employment opportunities, reducing the unemployment rate (RUAF 2019). Furthermore, urban agriculture also helps to reduce waste generated by utilising the organic waste for the urban farm, at the same time reducing the transportation and food waste from rural farming (FAO 2019). Figure 4 shows how a local food system works.

There are different types of urban agriculture depended on the purpose and context of the implications such as community gardens, street landscaping, front lawn, back garden, vertical farming, rooftop farming, forest gardening, greenhouse or green walls (Spacey 2017). Each type of urban farming has different advantages and disadvantages as well as the specific benefits which could be used in various environment. Among them, the green wall and green rooftop are two typical designs of the biophilic city which will be discussed below.

7 Green Wall

Green walls are building elements designed to support living vegetation which can improve a building’s performance (Manso 2015). The implementation of green roofs and walls remains limited because of high costs and questions over their utility (Steele 2017). Nonetheless, in the modern world of architecture, in order to create healthy, ecologically responsible buildings, green walls are emerging as important additions to the palette of construction techniques. Green walls are external or internal vertical building elements that support a cover of vegetation rooted either in stacked pots or growing mats (Greenroof 2020).

Green walls may also have other forms which could include ponds and fish. It could be used for the purpose of decoration or be incorporated into the cooling strategy of a house, as a kind of evaporative air conditioner, and they may even be designed as part of a water treatment system (Phillip 2013). With the simple version of a green wall, it can be made on a low-tech do it by yourself basis or it could be quite sophisticated and expensive. An increasing number of proprietary green wall systems incorporate irrigation systems (Downton 2013). Figure 5 is an example of a green wall facade in Swizerland. Then the examine of green roof also provides more insights to understand its possitive contribution in the benefits of biophilic city.

8 Green Rooftop

A green roof is a roof surface, flat or pitched, that is planted partially or completely with vegetation and a growing medium over a waterproof membrane (Greenroof 2020). Or “A green roof is a layer of vegetation installed on top of a roof, either flat or slightly sloped” (National Park Service 2017). Green roofs are very famous in modern buildings in Europe, with some countries such as Austria and Germany making it a mandatory requirement in their building laws. These countries have the Federal Nature Protection Act, the Building Code, and state-level nature protection statutes to promote and guide the implementation of green rooftop. Australian examples are less common but in 2007 a national organisation (Green Roof Australia) was formed to promote green roofs, and Brisbane City Council included green roofs in its proposed action plan for dealing with climate change (Downton 2013). The City of Melbourne has the “Growing Green Guide” to help the residents toward a green future (Figure 6) (City of Melbourne 2018). This guideline provides a details structure and framework to set a roadmap for Melbourne a achieve a green future with green architecture designs and buildings.

The green rooftop could be the rooftop garden, rooftop farming, or just simply the green grass on the roof. It creates a protective layer against the sunshine, creates positive impacts on climate such as lowering the building’s temperature by shading it, reduces the pollution, and also contributes in the biodiversity (City of Melbourne 2018). Green roofs can be quite effective in several applications in urban environments, where they can compensate for the loss of productive landscape at ground level as well as climate change. These green areas provide the rainwater buffer, it can purify the air and regulates the temperature as well as purifies the air, therefore, it can save energy and improve biodiversity in the city as the green roofs are part of climate proof construction. Rooftop farming is also another form of urban agriculture that can contribute to the urban solution on food demand (FAO 2019).

Above are the key concepts including but not limited to the green urbanism/biophilic city. They are not the separated elements of a biophilic city to stand alone but have the close connection to each other. Each of the components play a significant role in forming a biophilic city. The relationship and the role of each elements depend on different contexts and circumstances. Even though each element has its own function but when they interact with each other within the system, their roles also vary depend on the implication in specific environment. The advantage and disadvantage of each element can support each other in the system to be strengthen as a unique system which can adapt with each environment. Next chapter examines four benefits of biophilic city which are environmental, social, and cultural, economic, and health benefits.

Read more about Urban Agriculture here: https://phanexperience.com/?p=343

Part 1 of this article here: https://phanexperience.com/?p=306